In 1996, a small, family owned pharmaceutical company called Purdue Frederick began production of a seemingly innocent drug known as OxyContin. The drug was an opioid, stronger than nearly every other prescription painkiller on the market. Opioids as strong as OxyContin were previously intended for patients with absolutely unbearable pain, such as those living with terminal cancer. However, the marketing arm of Purdue Frederick, Purdue Pharma, insisted that OxyContin was different. This was a drug that was designed for a group of people that Purdue claimed had gone forgotten by the American pharmaceutical industry: chronic pain patients. Chronic pain was an under treated epidemic, they said, and OxyContin was the effective but safe opioid that these patients were looking for.

So, that is exactly what they told physicians. They sent sales representatives across the country to sell as much OxyContin as possible, seemingly with the intent of helping chronic pain patients. However, starting in the early 2000s, some reports of abuse began to pop up. Reports of the drug being crushed and snorted or stolen from pharmacies slowly accumulated. Purdue ignored the problem, insisting that OxyContin was still more helpful than it was harmful. They kept selling, until the lawsuits started. When individuals, physicians, and eventually states started suing the company, Purdue Pharma insisted that they had no idea of the addictive nature of OxyContin and that they were just trying to help deprived patients.

However, in 2018, journalist Barry Meier reported that a confidential investigation by the Department of Justice report found that company officials were fully aware of the addictive nature of OxyContin, but continued sales in the face of this knowledge. Through employing unethical and illicit marketing incentives, targeting vulnerable areas and individuals, and directly lying about the addictive nature of OxyContin, Purdue Pharma and its executives misled America and hooked a nation on a lethal drug, eventually escalating to the American heroin epidemic. The American opioid crisis is an incredibly complex issue, and there are significant debates about the true causes as well as drawbacks to higher regulation of prescription opioids. However, Purdue Pharma is directly responsible for the escalation of the epidemic and the American government needs to recognize this and take action to protect American citizens from the harm of the company. Although Big Pharma may not be the only cause of the opioid epidemic, Purdue Pharma’s deception of the market is the central cause.

Purdue Takes Advantage of Whoever They Can

Although there is not one general consensus among those who support the pharmaceutical industry and their role in the opioid crisis, their central rebuttals are that the crisis itself is exaggerated, higher regulation is more harmful to chronic pain patients than it is helpful, and the crisis is actually the fault of those prescribing the medication. However, despite the claims of opponents, Purdue was the central cause of the opioid epidemic due to the immeasurable damage and pain that they caused. Purdue’s aggressive and unethical marketing of OxyContin knowingly led to heavy over-prescription and high addiction levels. Purdue targeted specific doctors known for over-prescribing and pressured them to prescribe OxyContin to their patients by directly lying to physicians about effects of the drug.

In her book Dopesick: Doctors, Dealers and the Drug Company that Addicted America, investigative journalist Beth Macy investigates the origins and contributing factors to the opioid crisis. She found that when Purdue first began OxyContin production in 1996, they found doctors that were more likely to overprescribe the opioid and sent sales representatives after them. Macy explains that “if a doctor was already prescribing lots of Percocet and Vicodin, a [sales] rep was sent to deliver a pitch about OxyContin’s” effectiveness (Macy 32). The more likely a physician was to prescribe OxyContin, the more sales reps interacted with that physician. Not only did Purdue strategically target doctors who they knew would make them money, they also lied about the effects of OxyContin for profit. In the lawsuit filed against Purdue Pharma by the state of Vermont in 2018, Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan said that “Purdue convinced the medical community and the public to believe unsubstantiated statements” about how safe their opioids actually were (Donovan 2).

This is all only the foundation of Purdue’s marketing practices. No matter where they were or who they were trying to sell to, when trying to sell OxyContin Purdue Pharma strategically targeted doctors who would make them money and purposefully lied to them to do so. Purdue’s abusive practices only build up from here. Additionally, their sales representatives were heavily encouraged to lie to physicians and to stay quiet if they encountered any malpractice. When the state of Virginia sued the drug manufacturer, State Attorney General Mark Herring accused Purdue of having “an Incentive Bonus Program that deterred sales reps from reporting overprescribing healthcare providers,” (Herring 2). This signals that manipulative strategies were not only widespread company policy but were actively rewarded by the corporation. Purdue was fully aware of the damage that they were actively causing but continued to do so for increased profits.

Finally, the company also targeted specific geographic areas with high disability and Medicaid rates, especially old mining towns on the east coast, where there was a higher concentration of vulnerable patients. In her investigation, Macy discovered that one of the first places to encounter a serious OxyContin problem was Lee Country, Virginia, a town of about 20,000 people which was originally established for mining and is now filled with shut down factories and disabled workers. In the late 1990s, Purdue was sending Lee County the same amount of OxyContin pills as it was to “areas five times the size” (Macy 52). Macy points out that common risk factors for addiction “include poverty, unemployment, [and] multigenerational trauma,” all of which are higher than the national average in Lee County (Macy 128). This adds on to the list of Purdue’s unethical marketing practices. Not only did the company target doctors they knew would be susceptible to their sales reps, they targeted vulnerable individuals. The pharmaceutical company found the regions filled with disabled, impoverished and unemployed Americans and exploited their vulnerabilities, addicting a region to a drug suitable only for terminal cancer patients, and then made billions of dollars off of the suffering of American citizens.

The Snowball Effect: Purdue’s Effect on People’s’ Lives

After their manipulation of the market to get thousands of people addicted to OxyContin, Purdue’s actions in escalating the opioid crisis led directly to the modern heroin epidemic. For many heroin addicts, OxyContin and other prescription painkillers acted as a gateway drug, and they moved to heroin once the patients either built up a tolerance or OxyContin became too difficult to access. Macy spoke to multiple addicts who went through this process, one saying that “the pills either went dry or were just too expensive to get. And everybody who used to deal pills started dealing heroin instead” (Macy 133). Others reported to her that they all got to their heroin addiction the same way, “through prescription opioid pills” (Macy 127).

Although Macy was not able to interview every single American heroin addict, her research is indicative of a general trend that heroin addicts often start with prescription painkillers. Through their direct targeting of vulnerable individuals and communities, the company hooked thousands of patients on OxyContin and once the federal government finally made it more difficult to get a hold of in the late 2010s, forced those patients to turn to harder drugs, such as heroin. In her investigation, Macy describes heroin silently seeping into towns like Lee County, abused, taken advantage of, and subsequently left to rot by Purdue Pharma. All of the heroin addicts Macy interviewed were from Lee County or surrounding areas.

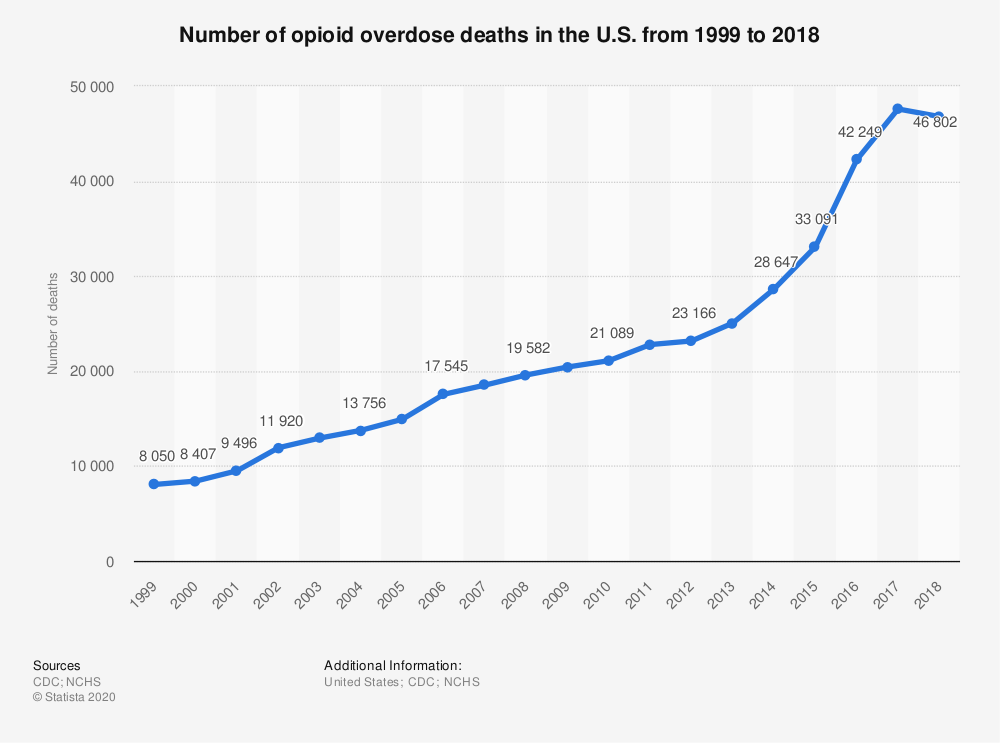

Purdue has faced consequences for their role in the American opioid epidemic, but the company as well as its owners continue to profit from their crimes to this day and will continue to do so unless further action is taken. Not only has it been proven that Purdue’s marketing practices were unethical and lead to skyrocketing addiction rates, but the selling of OxyContin correlates directly with the rise in overdose deaths in the United States. OxyContin was first placed on the market in 1996. The CDC reports that opioid deaths have risen from 8,050 in 1999 to nearly 47,000 in 2018 (CDC).

Purdue In The Public Eye

As Purdue pushed their drug across the country and opioid sales skyrocketed, so did opioid overdoses. The hundreds of lawsuits since the early 2000s which have forced Purdue to pay millions in settlements, Purdue still made a fortune from revenue from OxyContin. In 2001, the drug made up 80 percent of the company’s 3-billion-dollar yearly revenue. (Warren and Rogers 2). However, eventually the lawsuits were too much for the company to keep up with, and they filed for bankruptcy in September of 2019 (Warren and Rogers 3). The agreement involved the family that owns the company, the Sackler family, transferring ownership of Purdue. They agreed to make the company into a for-profit “benefit trust that would provide 4-billion-dollars in drugs – some of which are used to save people from overdoses – to cities, counties, and states” (Warren and Rogers 4). This may seem like a win, with Purdue ownership being transferred out of the Sacklers’ hands and the company supposedly being used for good. But this does nothing to change the fact that the Sackler family remains one of the richest families in America, and they built their estimated 13-billion-dollar worth off of OxyContin (Warren and Rogers 1). Especially when the new drugs they sell are opioid reversal agents, they will continue to make money off of a solution to a problem that they themselves caused.

Purdue still profits off the crisis they caused and will continue to do so unless permanent action is taken to shut them down to prevent them from doing further damage. According to their website, as of early 2020 the company is beginning to provide a 3.42-million-dollar grant to a non-profit to help it in its development of a Naloxone nasal spray, an “opioid antagonist used to reverse the effects of a life-threatening opioid overdose” (Purdue Pharma 1). They claim that they will not make any money off of this specific agreement, but it still gets them something far more valuable: positive media coverage. After years of being negatively associated with the opioid crisis, Purdue is working to gain positive media attention for seemingly charitable actions in order to continue selling their products. They are effectively attempting to make the American public turn a blind eye to the crimes they committed over the past 20 years by claiming to be “committed to advancing patient care and public safety,” (Purdue Pharma).

Purdue Pharma Today

Purdue Pharma strategically and unethically targeted the most vulnerable patients and physicians, addicting hundreds of thousands of people to their drugs, and then proceeded to craft a multi-billion-dollar empire. Unfortunately, Purdue Pharma is not an outlier. The American pharmaceutical industry has been tearing down the most vulnerable for decades. Life-saving drugs like insulin have never been more expensive, and Doctor Peter B. Bach says that drug companies charge so much “simply ‘because they can’” (Kounang 3). However, recently, Purdue’s victims got a win. As of October 21, 2020, Purdue pled guilty to three different federal criminal charges, agreeing to pay 8 billion dollars and also agreeing to shutdown the company. Purdue will finally no longer be able to profit off of the suffering of vulnerable Americans. The company will also be definitively seen in their true light, as the company that abused the American population for over two decades. Although this doesn’t solve the hundreds of thousands of deaths and the million of lives uprooted because of the company’s actions, it is a step in the right direction in terms of reparations toward the victims. At the same time, this also doesn’t change how the Sacklers remain one of the most wealthy families in the country, and doesn’t effect the continued heroin and fentanyl epidemics, as well as misconduct by other Big Pharma companies. The US Government is taking a significant step in the right direction, but needs to continue to do the same with other Pharmaceutical companies to truly atone for the mismanagement of the opioid epidemic.

Balko, Radley. “The New Panic Over Prescription Painkillers.” Huffington Post, 9 Apr. 2012, www.huffpost.com/entry/us-painkillers-abuse_b_1263565. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

Donovan, TJ. “Vermont Sues Purdue Pharma for Its Opioids Marketing Practices.” Office of the Vermont Attorney General, Sept. 2018, ago.vermont.gov/blog/2018/09/05/vermont-sues-purdue-pharma-for-its-opioids-marketing-practices/. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation. “Smashing the Stigma of Addiction.” Hazelden Betty Ford, www.hazeldenbettyford.org/recovery-advocacy/stigma-of-addiction. Accessed 3 Mar. 2020.

Herring, Mark. “Unredacted Complaint Sheds Light on Sheer Volume of Prescription Opioids Purdue Pharma Pushed into Virginia.” Office of the Attorney General of Virginia, 5 Sept. 2018, www.oag.state.va.us/media-center/news-releases/1261-september-5-2018-unredacted-complaint-sheds-light-on-sheer-volume-of-prescription-opioids-purdue-pharma-pushed-into-virginia. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

Isidore, Chris. “OxyContin Maker to Plead Guilty to Federal Criminal Charges, Pay $8 Billion, and Will Close the Company.” CNN Business, CNN, 21 Oct. 2020, www.cnn.com/2020/10/21/business/purdue-pharma-guilty-plea/index.html.

Lyapustina, Tatyana, and G. Caleb Alexander. “The Prescription Opioid Addiction and Abuse Epidemic: How It Happened and What We Can Do about It.” Pharmaceutical Journal, June 2015, DOI:10.1211/PJ.2015.20068579. Accessed 3 Mar. 2020.

MacCallum, Elizabeth. “Sufferers of Chronic pain and the government’s war on OxyContin.” Maclean’s, 15 Mar. 2012, www.macleans.ca/society/health/the-latest-opium-war/. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

Macy, Beth. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors and the Drug Company that Addicted America. Little, Brown and Company, 2018.

McGinty, EE, et al. “Stigmatizing Language in News Media Coverage of the Opioid Epidemic: Implications for Public Health.” National Center of Biotechnology Information, July 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31122614. Accessed 2 Mar. 2020.

Meier, Barry. “Origins of an Epidemic: Purdue Pharma Knew Its Opioids Were Widely Abused.” The New York Times [New York City], 29 May 2018, sec. A, p. 1, www.nytimes.com/2018/05/29/health/purdue-opioids-oxycontin.html. Accessed 22 Jan. 2020.

“Purdue Pharma L.P. to Fund Harm Reduction Therapeutics, Inc.’s Work to Develop Inexpensive, Over-the-Counter, Life-Saving Naloxone in the United States.” Purdue Pharma, 5 Sept. 2018, www.purduepharma.com/news/2018/09/05/purdue-pharma-l-p-to-fund-harm-reduction-therapeutics-inc-s-work-to-develop-inexpensive-over-the-counter-life-saving-naloxone-in-the-united-states/. Accessed 11 Mar. 2020.

United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention. “Number of Opioid Overdose Deaths in The U.S. from 1999 to 2018.” Statista, Statista Inc., 30 Jan 2020, https://www.statista.com/statistics/798347/number-of-opioid-overdose-deaths-in-the-us/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2020.

United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention. “Opioid Overdose.” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 18 Oct. 2019, www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/index.html. Accessed 26 Feb. 2020.

Warren, Katie, and Taylor Nicole Rogers. “The Family behind OxyContin Pocketed $10.7 Billion from Purdue Pharma. Meet the Sacklers, Who Built Their $13 Billion Fortune off the Controversial Opioid.” Business Insider, 17 Dec. 2019, www.businessinsider.com/who-are-the-sacklers-wealth-philanthropy-oxycontin-photos-2019-1. Accessed 11 Mar. 2020.